Joseph Hooker’s Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya

This year sees the bicentenary of the birth of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) and in celebration the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew has brought out a new facsimile edition of ‘The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya‘.

The original publication was in three volumes, produced between 1849 and 1851, and became an unparalleled commercial success for Hooker. This new edition, with an introduction by Virginia Mills, Cam Sharp Jones and Ed Ikin, has been reproduced from an original held in the Library, Art & Archives at Kew and contains all three parts.

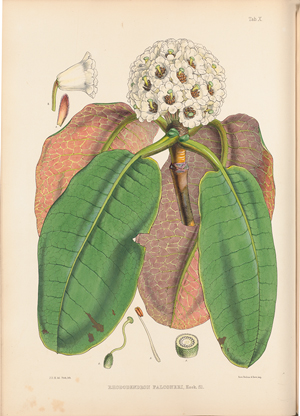

Holding this book is rather like holding a piece of history – it is beautifully produced and there is the thrill of looking at the facsimile of the original with the lavish illustrations that were produced by Walter Hood Fitch, accompanying the rhododendron descriptions. There are 30 plates and these are still considered some of the finest examples of botanical illustration ever produced. Fitch was one of the most talented botanical artists of the 19th century and his drawings in this book are magical.

Holding this book is rather like holding a piece of history – it is beautifully produced and there is the thrill of looking at the facsimile of the original with the lavish illustrations that were produced by Walter Hood Fitch, accompanying the rhododendron descriptions. There are 30 plates and these are still considered some of the finest examples of botanical illustration ever produced. Fitch was one of the most talented botanical artists of the 19th century and his drawings in this book are magical.

It is 170 years since Hooker made his trip to India, where he sought botanical treasures in the Himalayas. In the Introduction, Virginia Mills points out that travel to unexplored territories in the Himalayas, was, for Hooker, an opportunity to make his name through new discoveries. His notebooks are full of observations not only on plants but also on the wider natural world, horticultural and economic interest and surveying un-mapped areas.

The expedition was sponsored by Kew and they obviously expected a good return for their investment. As Virginia points out, Kew were not disappointed, for Hooker and his assistants collected over 5,000 species of plants as well as executing over 700 illustrations during the period 1848 to 1851.

His adventures certainly sounded exciting – at one point he was imprisoned by the Rajah, who had instructed the citizens of Sikkim not to give Hooker any food or provisions – his mapping exploits were considered by some to amount to spying (perhaps not unreasonably) and as he was the first European to be given permission to explore the region, the Rajah was understandably rather wary of him.

His adventures certainly sounded exciting – at one point he was imprisoned by the Rajah, who had instructed the citizens of Sikkim not to give Hooker any food or provisions – his mapping exploits were considered by some to amount to spying (perhaps not unreasonably) and as he was the first European to be given permission to explore the region, the Rajah was understandably rather wary of him.

Rhododendrons were the horticultural jewels of Sikkim but they were not easily collected. Hooker had to travel during monsoons, risk snow blindness in the higher mountains, suffer altitude sickness and was plagued by bites that often caused him ‘headaches that do not go off for hours‘. As an active collector himself he endured his share of hardship in pursuit of his plants. One of his more unorthodox practices was training his dog to bring him roadside shrubs but later he told his sister that he had also trained him to assist with his correspondence, so perhaps we need to take this literally.

Packing and transporting the valuable seeds and young plants was another challenge Hooker had to overcome. They were sent in tin boxes to preserve their longevity and protect them from damp and of course he used the Wardian Case for growing plants. He was certainly successful in this as in 1850 the Kew Annual report recorded receipt of ‘21 baskets of Indian orchids and new species of rhododendron‘, just one of many shipments, always accompanied by drawings of the plants.

Cam Sharp Jones outlines how Hooker and his father William (who was at that time Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and was editor of the three volumes) oversaw the publication while Joseph was still in India. The first volume published in 1849 received positive reviews both for the standard of the drawings and descriptions and the speed at which the information was being transmitted from the subcontinent.

The List of Subscribers is fascinating and is headed by HRH Prince Albert and includes the Dukes of Devonshire and Northumerland as well as the Duchess of Argyll, the Royal Library in Berlin and the University Library in Edinburgh.

Hooker’s impact on British Gardening is explored by Ed Ikin, who points out that Hooker’s introductions didn’t just enrich British gardening, they inspired a whole new approach to horticulture. With opposing poles in taste – from the mannered to the pastoral – the arrival of Hooker’s rhododendrons, such as the iconic Rhododendron falconeri (pictured above right) and R.Hodgsoni, (pictured left) heralded a new horticultural language – wild gardening – subsequently exemplified by William Robinson among others.

Hooker’s impact on British Gardening is explored by Ed Ikin, who points out that Hooker’s introductions didn’t just enrich British gardening, they inspired a whole new approach to horticulture. With opposing poles in taste – from the mannered to the pastoral – the arrival of Hooker’s rhododendrons, such as the iconic Rhododendron falconeri (pictured above right) and R.Hodgsoni, (pictured left) heralded a new horticultural language – wild gardening – subsequently exemplified by William Robinson among others.

Hooker was a confidante of Charles Darwin and ultimately became one of the most important botanists of the 19th century. He followed his father and became Kew Gardens’ most illustrious Director and his new species of rhododendrons came to play an important role in the evolution of British horticultural style.

Viginia Mills and Cam Sharp Jones are part of Kew’s Joseph Hooker Correspondence Project. Ed Ikin, is Head of Wakehurst Landscape and Horticulture.

If you love Rhododendrons you will definitely treasure this book as a wonderful souvenir and celebration of Joseph Hooker and his work on the rhododendron flora of the Himalayas.

‘Joseph Hooker’s Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya‘ by Joseph Hooker with illustrations by Walter Hood Fitch, Facsimile edition, is published in hardback by Kew Publishing at £25.00. (ISBN: 9781842466452).

(Review copy kindly provided by the publisher).

All photographs are © Kew Gardens.